By Deborah Nicholls-Lee

Gregory Crewdson

Gregory Crewdson

A new book and two new exhibitions explore the concept of the American Dream – and how it came to represent both a utopia and a dystopia.

“Sadly, the American Dream is dead,” Donald Trump told an audience of supporters when he announced his bid for the US presidency in 2015. “But if I get elected president, I will bring it back bigger and better and stronger than ever before.”

As the US elections of 2024 draw nearer, the American Dream is back on the agenda, with President Biden also promising to restore it, stating in a speech in November 2023 that “Bidenomics is just another way of saying ‘the American Dream’.”

First mentioned in print in the book The Epic of America (1931) by the US historian and businessman James Truslow Adams, the American Dream has become synonymous with social mobility and self-gain, and began, he wrote, as “a dream of a social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable”. With the 2020 Global Social Mobility Report

Today, the concept has found form in a range of extraordinary images, many brought together in Suburbia – Building the American Dream, a new exhibition at Barcelona’s Centre of Contemporary Culture (CCCB) that explores, museum director Judit Carrera tells the BBC, the “cultural history of the American suburbs” and “how architecture has implications that go beyond aesthetics”.

As US marines returned from World War Two, eager to settle down with their sweethearts, the American Dream of a family home far from the crowded tenements that characterised much of city living embedded itself in the national consciousness, aided by state propaganda campaigns promoting home ownership.

Benjamin Grant/CCCB

Benjamin Grant/CCCB

But the detached suburban home, with its neatly trimmed lawn and white picket fence, signified far more than a housing solution. It was a key component of the American Dream, reinforced by wholesome sitcoms such as Father Knows Best (1954-1960) and Leave it to Beaver (1957-1963). “It goes with the values of the meritocracy: you deserve a better future, you deserve a paradise,” explains Carrera, who is keen to stress the exhibition’s ambivalence about the idea of the American Dream, describing it as “both a utopia and a dystopia”.

Bill Owens/CCCB

Bill Owens/CCCB

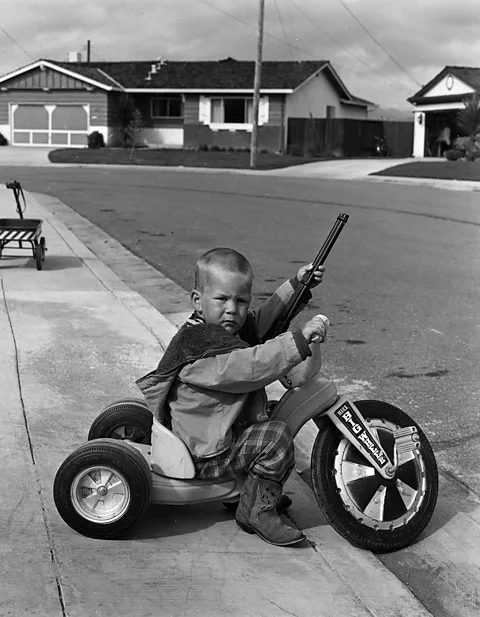

Indeed, cracks soon began to show in the idyllic lifestyle. “This model of a city that creates segregation” and “this idea of individual freedom”, explains Carrera, also “incentivised the fear of the other”. Doors were bolted, alarms were installed, and families took up arms. The iconic portrait of gun-toting four-year-old Richie Ferguson from the 1972 photo series Suburbia by Bill Owens (1938) captures this evolution, offering a glimpse into a dark future, unforeseen by Richie’s mother who told Owens, “I don’t feel that Richie playing with guns will have a negative effect on his personality.”

Gabriele Galimberti/CCCB

Gabriele Galimberti/CCCB

While nostalgic series such as The Wonder Years (1988-1993) continued to promote suburban life, a sense of encroaching terror was reflected in the rise of a new genre: the Suburban Gothic. Stephen King novels such as Carrie (1974) and It (1986), and films such as Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) and David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), made it clear that all was not well in paradise.

Merging the media of film and photography was the cinematically staged Twilight series (1998-2002) by US photographer Gregory Crewdson. This supernatural, Spielberg-meets-Hitchcock takedown of the American Dream, where every image looks like a crime scene, features as part of Gregory Crewdson – Retrospective at the ALBERTINA Museum in Vienna.

Gregory Crewdson/Albertina

Gregory Crewdson/Albertina

The equally unsettling Dream House series (2002) that followed is on show at the CCCB, and takes a look at the domestic dramas lurking behind the suburban idyll. In a nod to its silver-screen influences, Dream House features Hollywood actors such as Gwyneth Paltrow and Tilda Swinton as its central characters. The images hint at the hidden traumas of suburban life and how these housing developments miles from the city centre helped confine women to the domestic sphere.

The visual artist Weronika Gęsicka grew up in Poland during the fall of communism – a time, she tells the BBC, when there was an “overwhelming fascination with Western culture” and above all the US, which represented “an inaccessible world which one wanted to enter”. Gęsicka developed an interest in the commercial photographs of 1950s and 60s America, which, she says, “show a perfect, pastel world” and “a land of happiness”, much as some sections of social media does today.

Weronika Gęsicka/CCCB

Weronika Gęsicka/CCCB

Her work uses Photoshop to alter the images to reveal what she describes as the “scratches on that perfect surface” revealed “when we look closer”. In Untitled #52, from the Traces series (2015-17), the familiar US trope of smiling children welcoming their father home after work is disrupted by a broken path between them, suggesting that even suburban life comes with pitfalls.

Angela Strassheim/CCCB

Angela Strassheim/CCCB

The American Dream, it is suggested, has not necessarily brought fulfilment. The US photographer Angela Strassheim presents the all-American dining experience as something mundane (Left Behind, 2005) and, in Evidence (2009), she lets people know that their happy home was once the site of a murder. The American Dream property, she suggests in an image from 2005 (pictured above), cannot make you happy – instead, our greed has made it grotesque with tentacle-like balconies and balustrades.

Architecture critic and journalist Kate Wagner made a similar point a decade later when she launched her satirical McMansion Hell blog, unpicking, from an architectural perspective, the visual horrors of America’s most ostentatious and oversized homes. Annotating images taken by real estate agents, she critiques the ugliest properties where the American Dream has been taken to excess, pointing out a “Walt Disney ass door” and “poorly executed ceiling art“, for example, or a “giant honking wedding cake of a ‘cornice'” and a portico that “look[s] like it was lifted from a 2000s strip mall”.

Kate Wagner/CCCB

Kate Wagner/CCCB

Today, as the “big is better” mantra of the American Dream exacerbates global warming, the nightmare appears to be more real than ever. The large car parked out front – and the suburbanite’s reliance on it – has created a lifestyle, says Carrera, that is “completely unsustainable in the face of the current climate emergency”.

For the US war photographer Peter van Agtmael, if anything helped kill the American Dream it was the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; conflicts to which he was drawn as a photojournalist, but which left him with a poignant sense of disillusion. “I grew up benefiting from the American Dream, and I didn’t have much cause to question it,” the Yale graduate writes in his new book Look at the USA. That all changed when, post 9/11, he travelled to Afghanistan and Iraq. “I got to know soldiers in the field, and began to form friendships with them and visit them back in the US,” he tells the BBC. “That’s when I began to understand the real America, outside the confines of my bubble of privilege.”

Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

Van Agtmael’s photographs, such as the image of graffiti boasting about shooting an unarmed Afghan civilian, bear witness to the potential brutality of some US soldiers, and challenge what he describes as “a narrative of American goodness and righteousness”. Elsewhere, photos of a soldier with 40% burns (pictured above), and a US soldier’s widow choosing a headstone, document the scars left on the US that have altered its self-image.

Though Van Agtmael’s images are often critical of America, they are, he says, “born out of love and respect”. “I feel passionately about my country,” he says, “[But] I would wish for us to have a more honest dialogue about who we are.” For Van Agtmael and many of his contemporaries, the demise of the American Dream has created a sense of loss. “The myths I wanted to believe have largely been dismantled,” he writes in the epilogue to the book. “But there’s nothing to take their place.”