“It kind of started as a joke,” says producer and screenwriter Jemima Khan, “where I would say to my friends— particularly those that were close to their parents and had parents that were sane and functional— who would your parents choose [for you to marry]? And would it work with that person?”

More like this:

– Is the rom-com truly back?

– The best films to watch in February

– Marvel’s first Muslim superhero

That was the thought experiment that would eventually evolve into the film What’s Love Got to Do With It?, a funny, touching new romantic comedy starring Lily James, Shazad Latif and Emma Thompson. The story revolves around documentary filmmaker Zoe (James), an unlucky-in-love Londoner who is surprised to learn that her childhood friend Kazim (Latif) has opted for an arranged marriage. She convinces him to let her capture that journey for her next project, following him and his family the Khans all the way to his wedding in Pakistan with the chosen bride Maymouna (Sajal Aly).

What’s Love Got to Do With It? focuses on two friends, Kazim and Zoe, as the former goes ahead with an arranged marriage and the latter films him for a documentary (Credit: Alamy)

Propelled by zingy one-liners and engaging performances, the film is an enjoyable watch. James brings vulnerability to the spirited Zoe, while Latif is disarmingly charming as Kaz. The leads seem to be effortlessly at ease around each other, making it very believable that their characters are childhood friends. It isn’t surprising to find out that they have a longstanding friendship in real life too.

The film manages to colour within the familiar lines of the genre, yet still bring something unique to the table. The beats and conclusion are predictable, yet above it all is its exploration of Pakistani culture, and in particular the concept of arranged marriage, that makes it stand out. As Khan puts it, “I don’t think we’ve really seen much ‘Rom-com Pakistan’ before”.

That’s not to say there haven’t already been mainstream Western movies exploring romance involving Pakistani characters: British film East is East (1999) and US romcom The Big Sick (2017) are two of the more successful examples that come to mind. But, in showing a clash between Western and Pakistani values, they have often fallen back on stereotyping, and depicted arranged marriage in particularly broad brushstrokes.

What is arranged marriage?

Arranged marriage is essentially a union that is orchestrated by a third party, often the parents. As Dr NN Tahir, an assistant professor of Law at University College Roosevelt and a researcher at the Utrecht Centre for European Research into Family Law, explains, there was a time when this was the norm, even in the west. “In the olden days, people didn’t get to choose who they would marry. Marriage was seen as too important to be left to individuals; it was really a family or village matter. It wasn’t called arranged – that term really came into being when the concept of free marriage arose and became a frame for comparison – but elders, the people from your village, or even your employer would decide who you would marry.”

As Western societies became more individualised, so did the concept of marriage, with principles of free choice and autonomy often prioritised. Collectivistic cultures, as in Pakistan, still place great emphasis on the role of the extended family and wider community, so it makes sense that arranged marriages continue to be prevalent.

Within Western understanding, there is often a conflation of arranged marriages with forced marriages. While there are scholars who argue that there is a clear distinction between the two, Dr Tahir believes they are interlinked. “If you take arranged marriage as one organised by someone else, there could be a power differential that could slip into force. So, forced marriages can be seen as a category of arranged marriage – one that has gone wrong.”

However, even without force, there can be an element of coercion when it comes to arranged marriages – something those arranging the marriage should be aware of. And this isn’t always obvious. In the film, Kaz is an independent-minded, successful doctor who wouldn’t be forced into doing something against his will. Yet he is torn between his own wants and what he perceives to be his duty to family. “Don’t break our hearts again,” he is told by his grandmother. “All I want to do is be a good son,” he says. As Kaz puts it at one point, his and Maymouna’s marriage was “insisted” upon by her family rather than “assisted”.

Exploring this issue with complexity and nuance isn’t easy, particularly within the bounds of a rom-com. Movies such as East is East and The Big Sick present arranged marriage as an obstacle – replete with unrelenting parents and unsuitable candidates – for the characters to overcome in order to find true love. Unsurprisingly, these films have opened themselves up to criticisms of pandering to Western audiences and feeding into Orientalism. The practice of arranged marriage is often portrayed as something oppressive, outdated and strange – “exotic” even; inferior to and incompatible with Western values.

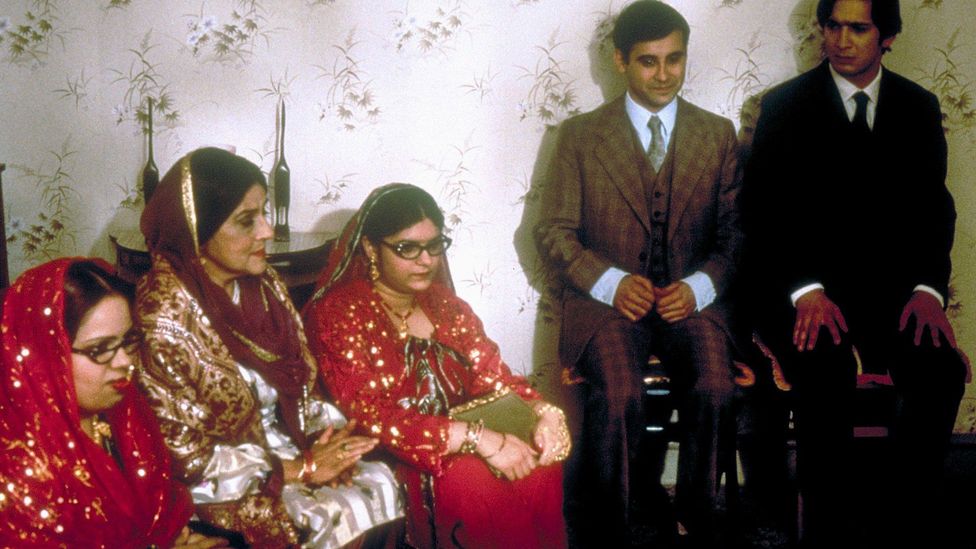

East is East is among the Western films that have portrayed arranged marriage in a stereotypically negative light (Credit: Alamy)

“The way arranged marriage is looked at through a Eurocentric lens is faulty,” says Dr Tahir. “What happens is that we take the autonomous style of marriage as the norm, and from that norm we look at the other marriage system – in this case arranged marriage. Because arranged marriage isn’t considered as ‘free’ as the autonomous marriage, it is already looked at negatively.”

However, What’s Love Got to Do With It? manages to avoid many of these pitfalls. It is Kaz himself who opts for an arranged marriage, and he’s actually attracted to Maymouna. The Khans, while not perfect and at times played for laughs, never veer into cartoonishly authoritarian family dynamics. Kaz’s mother, performed compellingly by Shabana Azmi, genuinely believes she is only doing what is best for her son – even though she doesn’t always get it right. Zoe’s relationship with her mother (Emma Thompson at her kookiest) is perhaps even more dysfunctional, and is never presented as superior or more enlightened than that between Kaz and his parents in any way. Many of the flaws of the “free” modern dating world are also laid bare.

“I was mindful, in particular, that the arranged marriage candidates should not be suboptimal – that the woman that is suggested by the parents is every bit a match for Lily James,” says Jemima Khan. “That’s why we cast Sajal Aly, who is such a brilliant actress and beautiful and vivacious. I think it was important to give her character agency but also to understand why Kaz thinks it’s a great idea. I loved The Big Sick, but in films like that and East is East, the arranged marriage candidates are really dire and not viable candidates for the central lead male.”

You can tell that Khan put a lot of thought into optics when penning the script. “A lot of my friends in Pakistan had been fed up with how it had been presented in the big TV shows and films like Homeland or Zero Dark Thirty, where they are always the ones depicted as the terrorists, or fanatics or backwards,” she says. “And so, I wanted to show a Pakistan that was a little more surprising, a little more colourful and joyful – a little more different than what we see in mainstream media.”

An informed viewpoint

Above and beyond writing the film, her first, Khan is an interesting figure in herself. While she isn’t Pakistani, she has a long and storied connection with the country. Her nine-year marriage to former cricketer turned politician, and later prime minister, Imran Khan was one of the most celebrated romances in Pakistan. Her children are half-Pakistani. She speaks Urdu fluently and immersed herself in the culture and history of her adopted country. On Twitter, she has joked about how every post is inundated with Pakistanis asking whether she still loves her ex-husband.

Latif cites her as one of the reasons he signed on for the film. “Jemima Khan, who my mom used to keep a scrapbook of, is a big figure in the Pakistani community. My uncles and cousins and people I know are obsessed with her. It was her handling of the script that I knew I could trust.”

There are little things throughout the film that could only have been written by someone with at least some modicum of insider knowledge, such as the awkward, stilted conversation between the prospective couple as the relatives watch or the subtle passive-aggressive dynamics between Kaz’s sister-in-law and his mother. As a British-Pakistani man who doesn’t drink or do drugs, I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been told, “I thought you’d be more modern living in London” by those that do in Pakistan (as Kaz is told by Maymouna). Or the number of times I’ve heard the one-liner “The Quran says if a man lies with another man he should be stoned” from gay Pakistanis as they smoke a joint (a quip repeated in the film by one of Maymouna’s wedding guests). Khan’s script doesn’t shy away from shining a light on some of the more problematic aspects of Pakistani society, such as the double standards when it comes to how women who marry outside the culture (like Kaz’s sister) are treated compared to the men. While I can see how that might be upsetting for some people, ultimately a portrayal of any culture shouldn’t have to be wholly positive, as long as it is fair. The fact that it is left to Zoe to highlight this injustice veers a little too close to white-saviourism for my liking, but at the end of the day, it is Kaz who brings the family back together.

What’s Love Got to Do With It? writer and producer Jemima Khan is a notable figure in Pakistan, thanks to her former marriage to Imran Khan (Credit: Alamy)

“One of the greatest concepts I learnt from my time in Pakistan is the concept of of intention or things being judged on intention,” says Khan. “I think most people that know me, especially those from Pakistan, know that my intentions are good and that I have an enormous affection for the country.”

There is a self-aware joke in the film when Zoe’s documentary gets cancelled because, in the words of her producers, “diverse subject, white lens”. However, in the case of What’s Love Got To Do With It?, while it is written by Khan, the person behind the lens is respected filmmaker Shekhar Kapur, who was born in Lahore, where the Pakistan scenes are set. Known for his lavish period dramas Elizabeth and its sequel, both starring Cate Blanchett, this is his first contemporary film set in the West. But it is the Lahore scenes that stand out: it is definitely one of the most beautiful portrayals of the city I’ve seen on the big screen, with rich, glossy and vibrant colours. The wedding scenes have dreamy aesthetics and fantastic dance sequences. Rom-coms aren’t often this visually stunning.

Kapur was “mindful about keeping it real,” he tells BBC Culture – as evidenced visually by the lack of clichéd, exoticising filters. “Obviously, every film has its own colour palette. But use a yellow filter? I’ve never done that. This is a film about real human beings. Any kind of yellow colour here, and suddenly that’s saying we’re in this distant land that we don’t understand. That’s not true. The people are the same… with the same ideas, the same ambitions, the same problems, the same inefficiencies. And so, for me to use a filter for Lahore would be like saying we’re talking about alien people. This isn’t a film about aliens. This is a film about people.”

So, in the end, what does love have to do with arranged marriages? According to Dr Tahir, if you only look at it from the perspective of romantic love, perhaps not much at first. But there is more than one kind of love. “My argument is that in an arranged marriage there are four types of love. One is the love the parent has for their child, then the love between friends, the love between siblings and the sensual love between individuals – which all come together in the course of the marriage.” These are all themes that the film explores.

By the same token, “the rom-com mythologised version of love… this idea that it can cure you and fix you and answer all your problems is quite problematic,” says Khan, “because it means our expectations are wildly unrealistic. And that’s a new thing. Love didn’t use to mean that.”

To the surprise of no one, Kaz and Zoe do wind up together – but only after Maymouna makes clear she is in love with someone else. Khan says it was important that it was Sajal’s character that rejects Shazad’s and not the other way around in order to counteract the problematic portrayals of brown women as somehow less desirable.

The search for love can often be a struggle, and there isn’t any guarantee of success no matter what route one opts to take. What’s Love Got to Do with It? doesn’t weigh in one way or the other about which version of marriage is better. All it asks is that audiences leave their preconceived notions at the door.